One of the great debates in the portfolio management space, both at industry and academic levels, centers around the merits of two popular tail-risk strategies: Index put option buying programs, and Trend strategies. Proponents argue that these approaches offer superior protection against catastrophic market events, but opinions diverge on which is more effective.

Defining the Strategies and Tail Risk Hedging

Tail risk hedging aims to shield portfolios from rare but severe market downturns. Such as Black Monday in 1987 or the 2008 financial crisis. Rather than seeking to outperform benchmarks, these strategies function as portfolio insurance, mitigating extreme losses and stabilising returns.

Trend-following strategies identify market trends- upward or downward- and position long or short accordingly. The way these trends are identified can vary, but the most popular seems to be use of moving average crossovers. For instance, a trader might buy corn futures when the 50-day moving average exceeds the 100-day average and sell when the trend reverses. Trend-following strategies are common in futures markets- covering interest rates, commodities, currencies and stock indices- and typically diversify across asset classed, time horizons, and managers. For example, the trend strategy used in the AQR paper that I will later cite not only includes the S&P500 or only the equity asset class, but also dozens of assets in multiple asset classes: equity index futures, government bond futures, currencies and commodity futures (averaging 1-, 3- and 12-month trends, and volatility-weighting between the constituent assets. This makes it a very diversified strategy in and of itself and accounts for the dispersion of returns often seen across trend strategies and asset managers that specialize in trend.

Surprisingly, Antti Ilmanen in his book ‘Expected Returns’ found that trend strategies have had a remarkably consistent track record in bad times. This may seem unintuitive as it is a relatively recent discovery (and something of a pleasant surprise) in the literature, and trend was initially conceived as a means of making significant uncorrelated returns rather than acting as a portfolio hedge.

Put strategies, on the other hand, involve systematically buying deep out-of-the-money puts. These are options with strike prices far below the market price, purchased to benefit from sharp market declines. This approach resembles an insurance premium: frequent losses on option premiums are offset by occasional large payouts when volatility surges.

The Debate:

The primary dispute lies in which strategy provides better protection. Antti Ilmanen and Cliff Asness of AQR advocate for trend-following as a less costly alternative to puts, while Nassim Nicholas Taleb of Universa Asset Management champions put options for their ability to deliver during extreme events.

Ilmanen argues that put options, while effective in crises, tend to drag long-term portfolio performance due to their high cost and negative long-term returns. Conversely, trend-following strategies, though imperfect as hedges, are more cost-efficient and offer positive average returns over time.

In a 2019 study by Michael Israelov—an AQR colleague—put strategies were found to deliver poor risk-adjusted returns. In fact, portfolios with a simple 60% equity and 40% cash allocation fared better during adverse conditions than those employing put strategies. The reason? Cash minimizes volatility without the consistent losses incurred by option premiums.

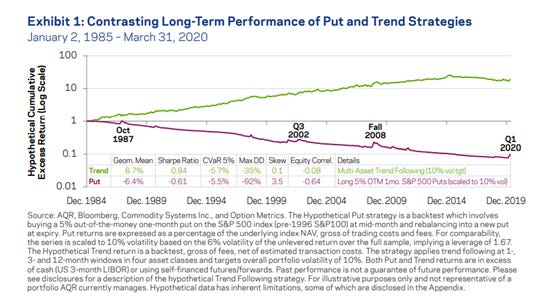

AQR's research further supports trend-following as a reliable, lower-cost hedge.(Antti Ilmanen, 2020). Their simulations compared monthly 5% out-of-the-money put purchases to diversified trend-following strategies, finding the latter consistently generated positive returns. In contrast, the put strategy suffered from significant underperformance—even though AQR generously excluded transaction fees for puts while accounting for trend-following fees.

Figure1: as you can see in the colored table, the Put buying strategy has very positive skew, meaning it loses money often but makes a lot of money on rare occasions (the rare occasions being high volatility periods here). This should typically be the return distribution of a good hedge hence the statement often used that it is a superior hedge but very costly,

Why Index Put Strategies Struggle

There are several possible explanations for why put strategies underperform. One argument is that the 35-year history of options data, although useful, is insufficient to capture enough rare, catastrophic events. Additionally, the period since the introduction of listed options has coincided with one of the longest equity bull markets in history.

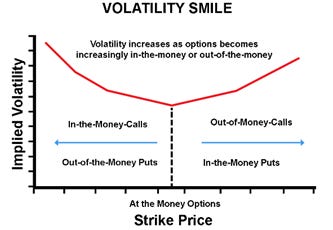

Another factor is that implied volatility—embedded in option prices—tends to overestimate realized volatility, making options relatively expensive. This discrepancy leads to the consistent “bleed” observed with put strategies, where premium payments erode capital over time. Furthermore, deep out-of-the-money options often trade at a premium because they price in crash risk, further dragging performance.

The volatility smile: as you can see, the deeper in or out of the money an option is, (generally speaking) the higher the implied volatility and hence the higher the price it trades at.

The financial economics school of thought also argues that insurance products such as puts must have an inherently negative risk premium such that an investor is penalized rather than compensated for holding them (unlike positive risk premium assets such as equities). This means that because their highest payoff comes when an investor needs the payoff most (during crises when risk assets are doing poorly), they must pay a premium for the asset and its return will as a result, be lower than the risk free rate on average.

These Index put buying strategies seem to only have enhanced performance when the portfolio manager has some sort of edge or skill with regards to identifying and timing these high volatility periods, such that they stay in cash (short-term, risk-free paper) when these opportunities are not present and then allocate heavily and with conviction when the signals they look at to signal higher future market volatility ‘flash red’, so to speak. This could lead to significantly eliminating the ‘bleed’ component of the strategy that is most responsible for its deeply negative returns. By bleed, I’m referring to the constant losses incurred on these options during low volatility regimes where these puts bought consistently lose value (leading to consistent capital losses), necessitating additional capital when rolling into subsequent periods to maintain the same level of protection. A whole cottage industry within the fund management industry has arisen to fill this niche of actively managed tail hedging, in fact.

Funds that actively trade volatility products but keep a bias towards downside risk hedging, hence making steady income when times are good (for example via partially hedged put selling strategies) while still maintaining the long put positions but having the discretion and skill to flip fully bearish and get more into these out of the money index puts when they sense that volatility is too cheap or that it could rise sharply near term. The selling point of these firms being that an investor gets the protection of a Put selling strategy when it matters, but with positive returns that are at least not a drag on the overall portfolio.

A Balanced Perspective

While put strategies offer strong protection during extreme market events, their persistent cost is hard to ignore. In comparison, trend-following strategies—though less precise in crisis scenarios—often benefit from upward trends in safe-haven assets like the Japanese yen, Swiss franc, and U.S. Treasuries. The key strength of trend-following lies in its ability to deliver positive returns across varying market conditions, not just during downturns.

Ultimately, the debate could be made more meaningful by comparing trend-following to a more sophisticated put strategy—one that dynamically shifts between cash and options based on market signals. For example, a model that increases put exposure only when volatility term structures are favourable would better reflect how many managers approach tail-risk hedging in practice.

Conclusion: Coughing baby vs Nuclear Bomb

(Ending the article on a humorous note)

The comparison between trend-following and put options is often reduced to simplistic arguments. Trend-following, with its systematic rules and diversification, is frequently contrasted with mechanical put-buying programs that ignore market conditions. But in reality, few managers blindly follow such naive strategies, given the well-known performance drag of static put allocations. A more constructive debate would compare trend-following with a sophisticated put strategy that adjusts based on market conditions and volatility forecasts.

In the end, both strategies have their place—trend-following offers steady, long-term gains with occasional crisis protection, while put options serve as powerful, if expensive, insurance against market tail events. Rather than dismissing one in favor of the other, savvy investors may find value in combining both approaches to build robust, all-weather portfolios.

Article by

Andrew Musembi